Along with 67 million other Americans, I tuned into Tuesday night’s presidential debate. In what might have been a questionable parenting decision, I allowed my kids to stay up and watch it with me. While we may not share every detail when they ask us political questions, they hear things in the car with us when we have NPR on and they come home with questions because of things their friends have said. So, we tell them the truth as best we can in age-appropriate ways.

And they knew the debate was coming, and they wanted to see it. So I baked cookies, we made popcorn. And they loved watching Vice President Harris’s side eye and even noticed how calm and collected she managed to stay in the midst of it all. I’m glad they got to have that experience with me, that I could answer their questions as they came up, and it was a pretty fun evening in a lot of ways.

But watching the debate with my children also made me so sad. It made me sad that I had to explain why so many of the things former President Trump said were not just unhinged and funny in how weird they were, but harmful and actually very dangerous. And it made me not just sad, but angry, that while my children know our family doesn’t think this is normal, it has nevertheless become the norm for political discourse in this country.

I know that what brings a lot of people to church is the hunger for community. And some come because they want support raising their children with a spiritual and ethical center. But I believe there are desperately needed things in this world today that congregations are uniquely equipped to offer First, congregations offer opportunities to make the world a better place. And second, we help people develop the inner skills and qualities to stay soft when that work gets harsh.

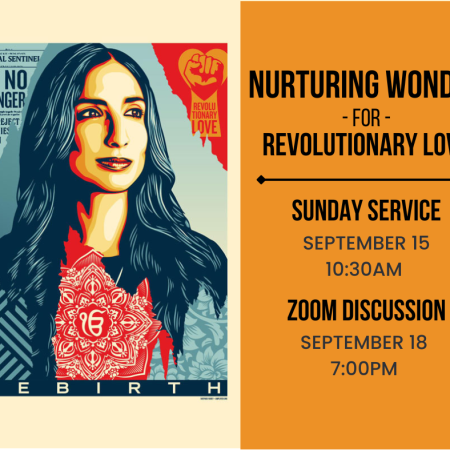

This need to heal our broken world without breaking ourselves is what led me to begin reading Valerie Kaur’s book. I decided to preach on a different chapter each month this church year because of how clearly she addresses the kinds of questions I’ve heard so many of you ask. How do I hold onto hope when it feels like the bullies keep winning? How do I nurture joy when I have to spend so much time in resistance mode? How do I keep love at my center when the world makes me so angry?

I know there are many here today who are deeply involved in the Get Out the Vote efforts. My spouse signed up to serve as an election judge, and I plan to offer rides to people who need help getting to the polls. Make no mistake, the coming election is crucial. But it’s also true that no matter who is elected on November 5th, this country will still be broken and love will still need our hands and feet when we wake up on November 6th. Valerie Kaur’s book offers ways to engage in the ongoing work for justice and equity that don’t deplete us, but rather help us to learn, grow, be changed, and be filled along the way.

I think what I love most about Valerie Kaur’s work is that she invites us not to change the world by trying to dominate others with our beliefs, our opinions, the rightness of our convictions. She invites us to move beyond the knee jerk temptation to categorize people as right or wrong, woke or not woke, good or evil. And she frames her approach in religious terms, pointing to her Sikh faith’s ideal of the “sant-sipahi, the warrior-sage. The warrior fights. The sage loves. It [is] a path of revolutionary love.”

And the first practice for revolutionary love she identifies is wonder. That feeling many of us have when we’re out in the forest or by the ocean, on a city rooftop at night, or gazing out the window of an airplane at the miniature structures and topography below. It can also be the feeling we have when holding a newborn baby, or listening as an elder talks about how the world was in a bygone era. And many of us experience wonder when we meet people who are different from us, yet with whom we still share a kinship, a sense of unity, a common interest, hope, or vision.

Kaur shares quite a bit about what it was like for her to grow up in agricultural California. Racism was ever-present and often painful and isolating. She became keenly aware that most people in her overwhelmingly white community saw her as “other” and did not relate to her as if they could imagine being in her shoes. And yet it is this capacity that’s so foundational to many religions, especially her Sikh faith. The very heart of Guru Nanak’s teachings is the unity underlying all people. Or, as Kaur put it, “You are a part of me I do not yet know.”

This is important because when we can wonder about the lives and experiences of others, it opens the door to being able to love them. But when we stop wondering about others, when we just make assumptions about them, when we relate to them not as human beings but as other, as obstacles even, that opens the door to violence. Nations and empires have been built on the practice of othering people. She writes writes:

Sometimes I imagine: What if first contact in the Americas had been marked not by violence but by wonder? If the first Europeans who arrived here had looked into the faces of the indigenous people they met and thought not savage but sister, brother, [sibling], it would have been difficult, perhaps impossible, to mount operations of enslavement, theft, rape, and domination. Such operations depend on the lie that some people are subhuman. If they saw them as equals instead, might they have sat down and negotiated a shared future? Imagine institutions on this soil built on the premise of equality rather than white supremacy. Imagine the forms of community that might have emerged, and how that would have evolved through generations. What would my childhood have been then? I reach the limits of my imagination. The dream evaporates. What does it take to reclaim wonder now after so much trauma and devastation?

Racism and sexism, transphobia and the history of colonization and empire profoundly shape the way we have all come to see and experience our world. For Kaur, this is precisely why the practice of wonder is so powerful. Kaur writes:

In brain-imaging studies, when people are shown a picture of a person of a different race long enough for comprehension, it is possible for them to dampen their unconscious fear response. We can change how we see. We shouldn’t confuse this with suppressing our biased thoughts. Saying to yourself Don’t be racist, don’t be racist doesn’t work. It actually increases the frequency and power of the original biased thought! Instead you have to choose to think of the face in front of you as belonging to a person… Therefore, when we encounter each other throughout the day, it is not our primal reflect that we are responsible for – it is the succession of conscious thought.

So Kaur began a simple practice to train her brain, to take responsibility for the succession of her conscious thought. As she lived her life each day and came across the faces of people she’d see in the grocery store, on TV, or on the Metro, she would say in her mind Sister. Brother. Sibling. Aunt. Uncle. And she would take a moment, and begin to wonder about each of them as a full human being. “When I do this,” she writes “I am retraining my mind to see more and more kinds of people as part of us rather than them. I practice this with animals and parts of the earth, too. I say in my mind: You are a part of me I do not yet know.”

This is such a simple but compelling practice. Especially in a world where schools face bomb threats, parents decide to keep their kids home for the day, and people face threats of violence because a presidential candidate repeated a lie in a debate about immigrants eating pets. Especially in a world with moneyed interests who are very invested in an us versus them mindset. In this context, practicing wonder – developing our capacity to sense the humanity in every other person we meet – isn’t about the Hallmark card version of love, it’s a practice of revolutionary love.

But, as Kaur writes, this practice also comes with responsibility. Because, as she writes, “if you choose to see no stranger, then you must love people, even when they do not love you. You must wonder about them even when they refuse to wonder about you. You must even protect them when they are in harm’s way.”

This Wednesday, September 18 at 7pm on Zoom I will lead a discussion about the first chapter of Valerie Kaur’s book. I hope to see many of you there. Because while we can practice wonder and love in revolutionary ways as individuals, this work is really only sustainable in community. She writes:

To be a person of color in America is to live on the precipice – any moment your world can erupt in violence. But this isn’t a problem just for people of color – or Americans. We all live under the cloud of potential violence as long as we live in a society that enforces hierarchies of human value, where violence is often perpetuated by institutions of power. Individual acts of love are not enough. We need to be part of movements that help us wonder, grieve, and fight together.

There are many reasons why this congregation exists, but for this time, I think it’s one of the most important. And it’s why UUCSS joined Action in Montgomery. So we could meet people of other faiths and many backgrounds to build power and change policy so this county and the state of Maryland are places where everyone can flourish.

I’d like to close with a very short meditation exercise that Deb Weiner led at yesterday’s retreat of your Board of Trustees. I’ve adapted it ever so slightly, but it was a powerful practice for Board members and I hope it’s powerful for you as well.

I invite you now to close your eyes and allow yourself to rest comfortably in your seat. Take a deep breath and let it out slowly, feeling your body relax more with each exhale.

Bring to mind our whole congregation, sitting here in the Sanctuary, joining us from many places on Zoom right now and later when they watch the You Tube video. Think of all of the people here, not just your friends and loved ones. But the people who disagree with you on things you care about. The people who sometimes annoy you. People here you maybe even avoid.

Visualize those persons or people and repeat the following phrases silently to yourself, directing the phrases to the people in your mind’s eye:

You are my sibling, my brother, my sister.

You are my beloved.

You are my neighbor.

You are part of me I do not yet know.

May you be heard and understood.

May you feel valued and respected.

May you know you are held always in love beyond belief.

Now, take another deep breath, arriving back to the service, to one another here and now. Thank you.